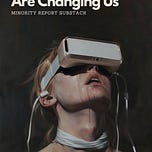

In the age of hyperconnectivity, algorithms no longer just suggest our next video or curate our news feed. They have become architects of perception, subtly and systematically reshaping who we are, how we think, and what we value. We are no longer simply using technology. Technology is, quite literally, using us.

At the heart of this transformation is a simple but powerful function. The algorithm’s purpose is to capture and retain our attention. Whether it is YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, or Twitter, the success of a platform depends on how long we stay engaged. To optimize for attention, algorithms have two paths. The first is to become better at predicting our needs, wants, and interests. The second is more sinister: to manipulate us into becoming more predictable.

Predicting vs. Manipulating: Two Sides of the Same Coin

The first strategy, which is prediction, is technically challenging. It requires vast amounts of personal data, sophisticated machine learning, and nuanced behavioral models. The algorithm must learn our desires, our habits, and our weaknesses. But this method comes with a significant liability. It relies on voluntary participation. Users must continue feeding the system by scrolling, sharing, liking, and commenting. And that is risky. We might burn out. We might delete the app. We might install screen-time blockers or create digital detox routines. In short, we might stop cooperating.

That is why the second strategy, which is manipulation, is so effective. Rather than adapt to the messy complexity of human behavior, the algorithm nudges us toward simplicity. It does not try to understand the nuance of who we are. Instead, it nudges us toward becoming easier to understand, easier to predict, and easier to control.

Homogenization: The Shortcut to Engagement

To manipulate users into becoming more predictable, the algorithm employs a subtle but potent mechanism: homogenization. The more similar we are in beliefs, values, and reactions, the easier we are to categorize and anticipate. And so, rather than supporting the flourishing of diverse and complex individuals, algorithms push us into narrowly defined identity groups.

This does not mean that the algorithm wants everyone to think the same. It does not need total uniformity. Instead, it needs clearly labeled and easily segmented categories. Left versus right. Vegan versus carnivore. Pro-vaccine versus anti-vaccine. It only needs enough people to behave in predictable patterns. And once you are in a category, your feed begins to reflect and reinforce the values of that group. Not because it is good for democracy, but because it is good for retention.

This is how polarization emerges, not as an accident, but as a feature. When our worldviews become more rigid and less nuanced, our behavior becomes easier to predict. Our feeds become echo chambers. Our identities become tribal. And the algorithm becomes more powerful.

Values Are Not Fixed but Formed

This process is not just technological. It is deeply psychological. Contrary to popular belief, values are not internal, preexisting principles that guide behavior. Rather, values emerge through repetition. The more consistently we act in a certain way, the more those actions crystallize into habits, then into character traits, and eventually into the core of who we are.

This means we do not think our way into new values. We act our way into them.

So when we consistently engage with inflammatory content, when we repeatedly like, share, and comment on messages aligned with a particular worldview, we do not just signal our values. We form them. In this way, algorithms become the silent engineers of value systems. They do not need to convince us of anything outright. They only need to shape what we pay attention to.

Attention Shapes Reality

There is a scientific basis for this. In neuroscience and cognitive psychology, it is well established that attention is not passive. It is an active, reality-shaping force. What we focus on determines what we perceive, what we remember, and ultimately what we believe to be true. Attention literally rewires the brain. Neural pathways strengthen through use. This is the foundation of habit formation.

The more we engage with certain content, the more dominant it becomes in our cognitive landscape. Over time, we develop emotional and ideological attachments to those patterns. Eventually, they harden into identity.

The Feedback Loop of the Attention Economy

Digital platforms exploit this principle with ruthless efficiency. They prioritize content that triggers our strongest emotional responses, especially fear, anger, and outrage. These emotions boost engagement, increase screen time, and make us more reactive. Because we act on them by clicking, commenting, and arguing, they also become part of how we see ourselves.

Take, for instance, the rise of toxic masculinity in online communities. Algorithms learned that content promoting dominance, aggression, and misogyny garnered massive attention among young men. As a result, users were repeatedly exposed to these narratives, not just as passive spectators but as participants in a growing cultural movement. Over time, exposure turned to endorsement, and endorsement turned to identity.

The same mechanism was exploited in politics. Donald Trump’s campaign strategy was not just to inform or persuade. It was to mobilize anger, particularly among disaffected groups. By doing so, he turned political engagement into an emotionally charged performance of identity. The January sixth insurrection was not just a political event. It was an identity crisis made visible, enacted by individuals whose values had been forged online through repetition and affirmation.

The Twenty-Five Percent Rule: How Norms Tip

But the algorithm does not need everyone to believe the same thing. Behavioral science suggests that when a committed twenty-five percent of a population adopts a new belief or norm, the rest will eventually follow. This is the tipping point, the moment when minority values become mainstream.

Understanding this, the algorithm does not try to create one monolithic worldview. Instead, it seeds multiple, compartmentalized ones. It nurtures smaller, highly engaged communities with strong identities. These groups are more likely to take action, share content, and influence others. In this way, the algorithm does what evolution always does. It experiments with variation and amplifies whatever gets the best results.

So we are not becoming more alike. We are becoming more divided, into groups with stronger internal coherence and deeper external opposition. This fragmentation allows for efficient prediction and control. It will continue, so long as one group wins over the others, because dominance is the ultimate form of predictability.

Reclaiming Our Attention and Rebuilding Our Values

But if the same systems that hijack our attention can shape harmful values, they can also be reclaimed. We are not passive victims of the algorithm. We can choose to participate differently. We can act our way into better values, values rooted in empathy, interconnection, and care for all beings.

This requires intentional action. We must create new habits that reflect the values we want to cultivate. We must build platforms and practices that reward curiosity instead of certainty, reflection instead of reaction, and cooperation instead of competition.

It also requires collective agency. Just as toxic behaviors go viral, so can regenerative ones. Just as online communities form around outrage, they can also form around justice, compassion, and stewardship.

Perhaps most importantly, we must recognize that the fight for attention is a fight for reality itself. What we pay attention to becomes what we care about. What we care about becomes who we are.

The Future Is Not Algorithmic Unless We Let It Be

We are standing at a crossroads. One path leads to deeper polarization, commodified identities, and engineered outrage. The other leads to a more intentional, values-driven society, one where technology serves our shared humanity rather than the other way around.

To move forward, we must ask ourselves what kind of people we want to become. What values do we want to embody? And how can we reclaim the tools that have been used to manipulate us in order to instead empower us?

The algorithm is not inherently evil. It is a mirror. It reflects back what we feed into it. But it also nudges. It reinforces. It shapes. In doing so, it becomes a co-author of our shared reality

.