Beyond Growth, Towards Alignment

A strategic framework for aligning degrowth, wellbeing, and doughnut economics into a credible path for systemic change By Erin Remblance & Kasper Benjamin Reimer Bjørkskov

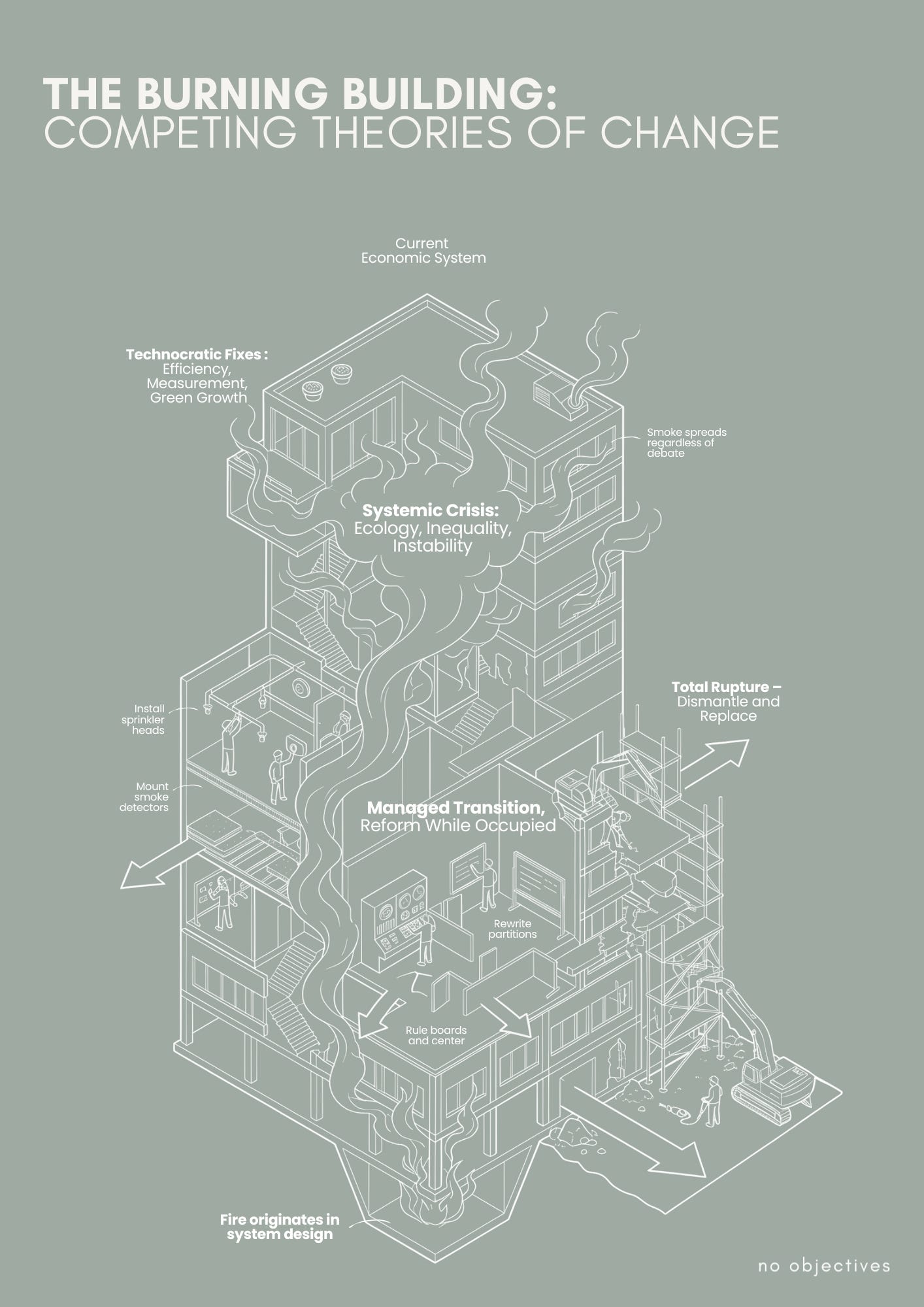

Imagine being trapped in a burning building where everyone agrees something is wrong, but no one agrees on what to do next.

One group wants to put out the fire. They argue that if we install better sprinklers, use fire resistant materials, and measure heat more accurately, the building can be saved. Another group says the fire is a symptom, not the problem. The building itself is unsafe. It was designed to burn. Their answer is to leave, tear it down, and build something entirely different. A third group insists we can stay inside while slowly renovating, room by room, as long as we change the rules for how the building is managed.

While these arguments unfold, smoke continues to spread through the hallways.

This, in many ways, is where we are today in debates about the economy. We agree the system is in crisis, ecological collapse, rising inequality, political instability. But we are deeply divided over how change happens. Should we fix the system from within, redesign its metrics and incentives, and hope it adapts? Should we dismantle it and build something fundamentally different? Or should we attempt some careful mix of both?

To make sense of these disagreements, we have produced a growing vocabulary: growth, green growth, wellbeing economy, doughnut economics, degrowth, post growth. Each term comes with its own reports, conferences, champions, and critics. Yet instead of helping us coordinate action, this expanding language often fragments it. The debate turns inward. The movements splinter. And the system we are trying to transform continues largely untouched.

This essay is about why economic terminology has become a hindrance rather than a help, what the real differences between these ideas actually are, and how they can work together rather than against each other. But to do that, we first need to understand what we are up against. Because this confusion is not accidental. It mirrors a far more deliberate and successful strategy that reshaped the global economy over the last seventy years.

What We Are Up Against: How Ideas Became Power

After the Second World War, most Western countries embraced a Keynesian economic model. Governments played an active role in steering markets. Strong welfare states expanded. Unions negotiated higher wages and better working conditions. Democracy, in practice, meant redistribution, public investment, and collective decision making.

To a small group of economists and business leaders, this was not progress. It was a threat.

Thinkers like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman believed that democratic politics inevitably led to inefficiency, inflation, and creeping authoritarianism. In their view, markets and corporations were better decision makers than voters and governments. They were more efficient, more innovative, and less prone to what they saw as the emotional excesses of democracy.

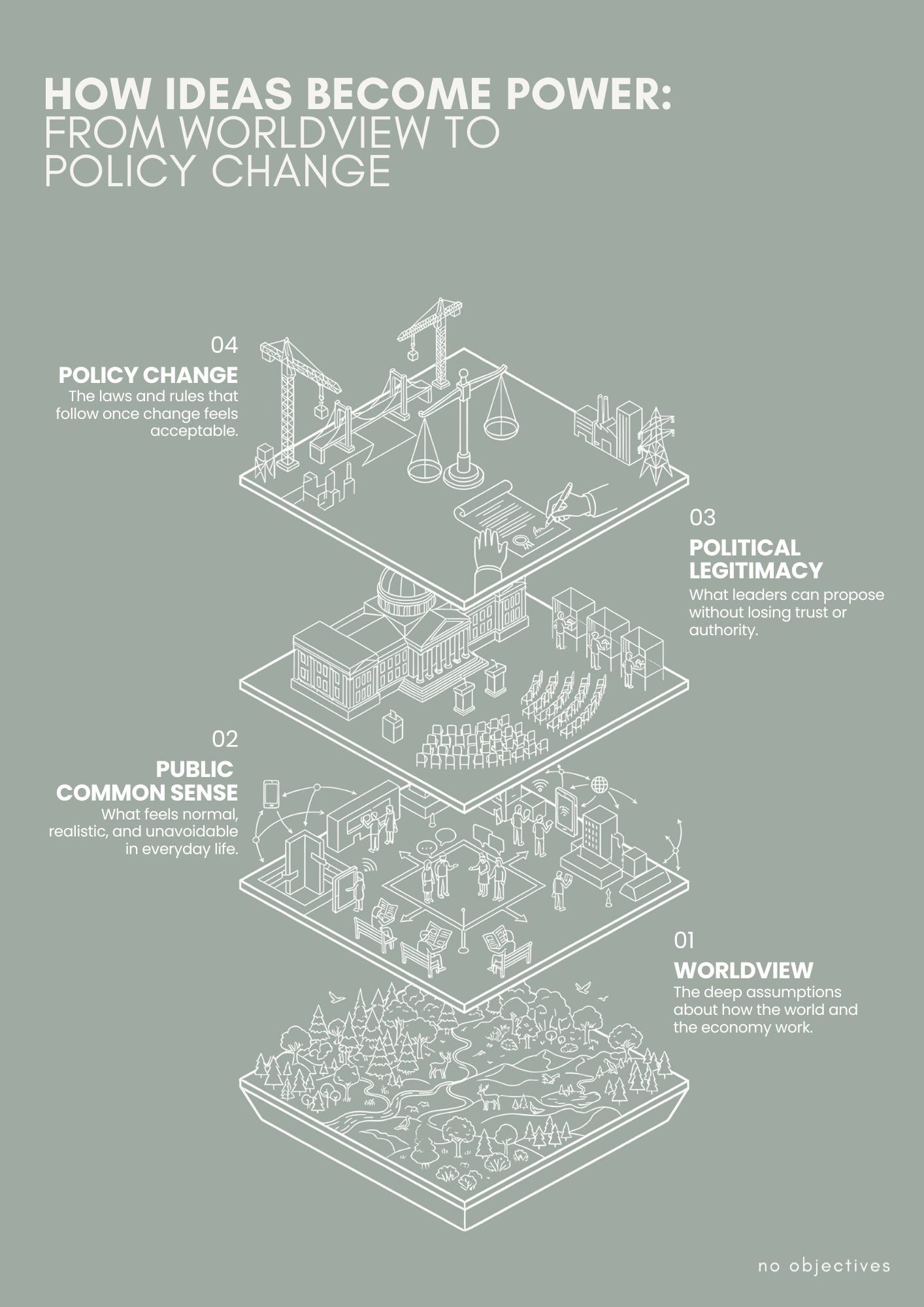

At first, these ideas were marginal. But their proponents understood something crucial: political power follows cultural power. If you change how people think about the economy, politics will eventually follow.

So instead of armies, they built an idea. They redefined freedom — turning markets into “freedom” and government into “tyranny.”

To enable this, shift Hayek gathered a small group of intellectuals in Mont Pèlerin, Switzerland. This meeting gave birth to the Mont Pèlerin Society, an ideological engine designed to shift the climate of opinion over decades, not election cycles. They did not start with policies. They started with a worldview.

In the United States, this intellectual project was given a corporate action plan. In 1971, Lewis Powell, a corporate lawyer who would later become a Supreme Court Justice, wrote a confidential memo to the US Chamber of Commerce. His message was blunt. Business should stop fighting individual regulations and start building permanent infrastructure. Think tanks. University chairs. Media outlets. Legal advocacy groups. A machine that could shape ideas, not just laws.

The Mont Pelerin Society provided the ideology. The Powell Memo provided the blueprint.

From Bullets to Belief: How Neoliberalism Went Mainstream

The first large scale experiment in neoliberal economics did not come through democracy. It came through force. In 1973, a US backed coup overthrew Chile’s democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. Under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, economists trained at the University of Chicago implemented radical privatization, deregulation, and austerity.

The result was brutal. Thousands were killed or disappeared. While neoliberal reforms were imposed, they lacked legitimacy. Violence could enforce change, but it could not sustain it.

So the strategy evolved.

In Britain, Antony Fisher, a follower of Hayek, founded the Institute of Economic Affairs. Instead of tanks, they used pamphlets. Instead of repression, persuasion. Complex economic theory was translated into simple, repeatable talking points. Journalists were given ready made stories. Politicians were handed policy proposals that appeared objective and inevitable.

By the time economic crises hit in the 1970s, the alternatives were ready. Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan did not invent neoliberalism. They adopted it. Thatcher later wrote that the Institute of Economic Affairs had created the climate of opinion that made her victory possible.

From there, neoliberalism spread globally through institutions like the IMF, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization. Structural adjustment programs enforced privatization and austerity across the Global South. What began as a fringe intellectual project became common sense.

Antony Fisher later scaled this strategy through the Atlas Network, a billionaire funded global web of think tanks that continues to shape policy debates today. Its tactics remain consistent: delay inconvenient science, deflect responsibility onto individuals, and distract with misinformation.

The core strategy can be summed up simply: change minds first, policy second.

The Irony: We Forgot the Lesson

Here is the uncomfortable truth. Many movements for economic transformation today are failing not because their ideas are wrong, but because they have forgotten this lesson.

Instead of building a shared agenda, they argue over terminology. Instead of clarifying theories of change, they collapse them into slogans. Instead of shaping the climate of opinion, they debate who owns the most correct word.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the confusion between degrowth, the wellbeing economy, doughnut economics, and post growth.

So let us slow down and untangle them.

Four Economies, Four Logics

First, the system we currently live in.

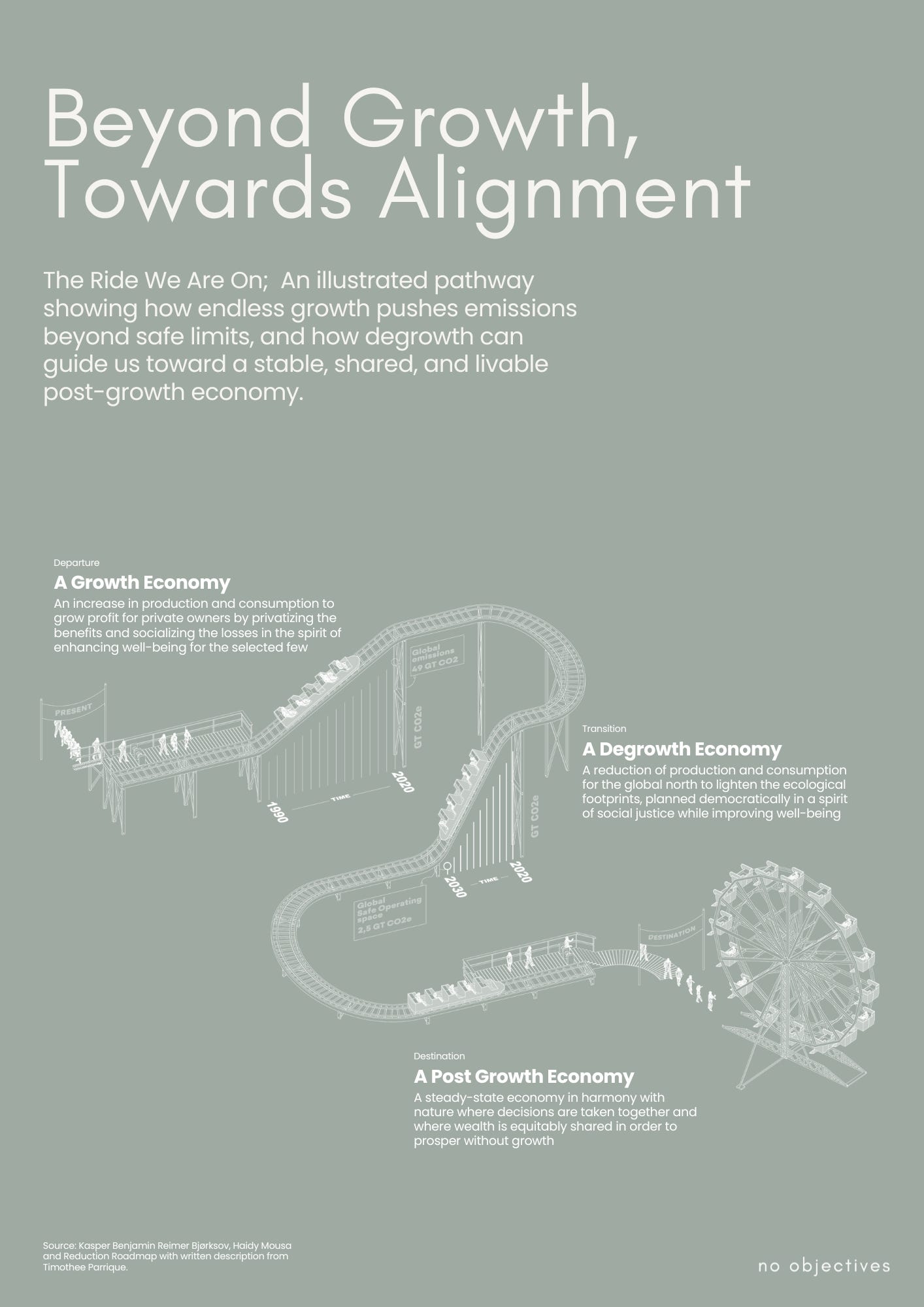

The present capitalist growth economy is defined by a simple logic: increase production and consumption to grow profits for private owners. Benefits are privatized. Costs, from pollution to social breakdown, are socialized. Growth is justified as serving wellbeing, but in practice it concentrates wealth and power among a small minority.

Degrowth is a transition strategy. It starts from the recognition that endless growth is incompatible with ecological limits and social justice. Degrowth calls for a planned, democratic reduction of production and consumption in wealthy economies, especially in the Global North. Its goal is to reduce ecological pressure while improving wellbeing through redistribution, care, and sufficiency. Degrowth is explicitly political. It confronts capitalism directly and challenges existing power structures.

Post growth describes the destination. A steady state economy in harmony with nature, where decisions are made collectively and wealth is shared equitably. It is an economy designed to prosper without growth.

The wellbeing economy is close to this definition. Conceptually, it aligns with post growth in rejecting GDP as the primary goal and in centering human and ecological wellbeing. In practice, however, it functions as a transitional vision rather than a confrontational strategy. It does not directly challenge power or capital. Instead, it seeks to gradually redirect the economy through new indicators, measurements, and policy priorities. Change is imagined as something that can occur quietly, from within existing institutions.

Doughnut Economics functions similarly. It provides a framework to measure whether societies are operating within a safe and just space between social foundations and ecological ceilings. It is explicitly post growth in its measurement. But again, it describes the destination more clearly than the journey.

All of these terms are useful. The problem is not their existence. The problem is how they are being used.

Why Words Become Weapons

The real conflict here is not semantic. It is about theories of change.

Degrowth treats transformation as a political struggle. It assumes that systems built on accumulation will not reform themselves out of existence. Power must be confronted, redistributed, and constrained.

The wellbeing economy and doughnut economics often rely on a managerial theory of change. Change what we measure. Change what we incentivize. Nudge the system, and behavior will follow.

There is an appealing optimism in this. Unfortunately, decades of evidence suggest it does not work on its own.

We have measured inequality for decades. It has grown. We have measured emissions while outsourcing them through global supply chains. We have classified biomass as carbon neutral and called it progress. Measurement adapts to power far more easily than power adapts to measurement.

If indicators truly threatened the system, they would never be adopted. Instead, they are selectively designed to remain compatible with growth.

This is why scholars have called degrowth and the wellbeing economy an odd couple. One repoliticizes sustainability. The other often depoliticizes it.

But here is the crucial point. They are not enemies. They are incomplete without each other.

Vision Without Process, Process Without Vision

Degrowth sometimes falls into what could be called the environmental movement fallacy: the belief that if change does not happen immediately and completely, it is not worth pursuing. But systems rarely change in leaps. They tip gradually. The wellbeing economy and doughnut economics provide something degrowth often struggles with: broad appeal and a shared vision. They help people see where we need to go.

Degrowth provides what they lack: a mechanism to get there.Setting targets is not enough. As James Clear puts it, we do not rise to the level of our goals. We fall to the level of our systems. Every country now has climate targets. Emissions still rise. The problem is not ambition. It is structure.

Degrowth is not about shrinking everything. It is about scaling down what is harmful and scaling up what sustains life. In wealthy countries, this means reducing overproduction and unnecessary consumption. In poorer countries, it can mean expanding access to housing, healthcare, education, and energy. Degrowth is about freeing up ecological space and ending exploitative economic relationships.

Without this process, visionary frameworks risk being absorbed into green growth narratives. Sustainable development has already suffered this fate. Without a clear break from growth, wellbeing becomes another adjective attached to business as usual.

Co optation: When a Vision Becomes a Sticker on the Same Old Machine

Here is where things get more urgent, and more practical. The wellbeing economy and doughnut economics are popular for a reason. They are hopeful. They sound human. They invite people in rather than pushing them away. They can be spoken in boardrooms and classrooms, parliaments and dinner tables. They offer an alternative to the cold, mechanical language of GDP and “competitiveness.”

This is often viewed as a positive attribute but many mistake adoption for transformation. They assume that if a word is widely adopted, it must be helpful for movement building. Yet adoption is not the same as transformation. When a term is so flexible that it can mean anything, it ultimately means nothing

That is exactly why they are being co-opted. Co-option does not usually look like a villain twirling a moustache. It looks like a press release. It looks like a new department. It looks like a glossy PDF with smiling families on the cover. It looks like an institution saying, “We agree,” and then continuing as before.This happens because both frameworks are, by design, made not to confront growth. They define a desirable outcome, meet everyone’s needs within ecological limits, but they do not automatically force a confrontation with the growth imperative or the power structures that enforce it.

That flexibility is a strength for coalition building. But it is also a weakness, because it allows powerful actors to adopt the language while quietly keeping the old rules.A wellbeing economy can become “wellbeing, plus growth.” A doughnut can become “doughnut reporting, plus business as usual.” The dashboard changes. The engine does not.

Doughnut Economics offers a compelling example as it is increasingly being co-opted by being used in exactly the way it warns against. The problem arises when a systemic diagnostic framework is repurposed to guide individual actors, projects, and organizations, even though the Doughnut explicitly shows that no single actor can operate within planetary boundaries on their own. In doing so, a call for collective, structural change is replaced with incremental adjustments at the individual level. Systemic limits become targets for local optimization, while the structures that drive overshoot remain intact.

And if you think that sounds cynical, it is worth remembering the historical pattern: when an idea threatens power, power does not usually ban it. Power absorbs it, sanitises it, and sells it back. Sustainable development is a perfect example. It started as a transformative concept. Over time, it became compatible with almost anything. Today, almost every corporation and government claims to support sustainability while the underlying system keeps extracting, expanding, and overshooting.

The same risk applies to wellbeing and doughnut frameworks unless they do something uncomfortable but essential: define themselves in a way that cannot be easily bent back into growth ideology. That means they must set clear definitions that include structural commitments, not just moral aspirations.

Why Appealing to Power Will Not Get Us There

This is the hardest sentence in the whole essay, because it demands a change in posture.

Trying to appeal to power will never get us there.A thousand years of history have shown this much. Elites rarely give up privilege because they are persuaded by moral arguments alone. They give it up when they are pressured, constrained, out organised, or when the legitimacy of the system they rely on begins to fracture.

Power can be negotiated with, yes. Power can be split, yes. But power does not transform itself out of kindness. If it did, we would not need labour movements, civil rights movements, women’s movements, anti colonial movements, or climate movements in the first place. We would simply publish well argued reports and wait for justice to arrive in the mail.

The wellbeing economy and doughnut economics are often presented as if the main barrier is misunderstanding. If leaders could only see the right data, the right metrics, the right dashboard, then they would steer the ship differently.

But the ship is not only steered by knowledge. It is steered by interests.

Changing indicators is not enough if the underlying incentives still reward extraction, concentration of wealth, and growth at all costs. Indicators can be adopted and ignored. Indicators can be designed to flatter progress while hiding outsourced harm. Indicators can become a form of reputation management.

So the wellbeing economy and doughnut economics must do more than nudge power toward transformation. They must be willing to confront it.

Not with purity tests, but with clear red lines.

If the framework can be used to justify continued expansion in already wealthy countries, it will be used that way. If the framework can be adopted without changing ownership, investment priorities, or material throughput, it will be adopted that way. If the framework can be turned into branding, it will be turned into branding. That is not pessimism. That is pattern recognition.

What Clear Definitions Actually Look Like

So what does it mean to define wellbeing economy and doughnut economics in a way that cannot be co opted?

It means saying explicitly what they imply about growth, throughput, and power. It means writing into the definition the parts that make them hard, not only the parts that make them popular.

For example, a wellbeing economy that is serious must be clear that wellbeing is incompatible with continued ecological overshoot. That means, in practice, absolute reductions in material and energy use in wealthy economies. Not only relative efficiency improvements.

A doughnut approach that is serious must be clear that meeting social foundations within ecological ceilings requires structural changes in production, consumption, and distribution. Not only better reporting.

In other words, these movements must move from “vision statements” to “guardrails.”

They can still be welcoming. They can still be broad. But they must be specific about what does not count as success.

Because if you do not define the boundaries, someone else will. Usually someone with more money.

Degrowth’s Mirror Lesson: Being Right But Rude Does Not Mobilise

If wellbeing and doughnut frameworks need more confrontation, degrowth needs a different kind of humility.

Degrowth is often right. Sometimes painfully right. It points directly at the structural contradiction of infinite growth on a finite planet. It names the political problem: capitalism’s dependence on accumulation. It refuses to pretend that nicer metrics will dissolve the growth imperative.

But degrowth can fall into a trap of its own: the belief that because the diagnosis is correct, the movement will follow automatically.

It will not.

Systems do not change overnight. People do not reorganise their lives overnight. Politics does not realign overnight. Movements win through sequencing, coalition building, and emotional intelligence. Not just through correctness. Degrowth sometimes carries what many people experience as a tone of scolding. A sense that if you do not accept the full analysis immediately, you are part of the problem. That posture may feel satisfying inside a small group that already agrees. It is not effective for mass mobilisation, which is what we desperately need.

Being right but rude is not a great strategy.

Not because truth should be softened, but because movements are made of people. People need a destination that feels worth it, a pathway that feels possible, and a community that feels dignified. If the first interaction someone has with degrowth is a lecture that makes them feel stupid, guilty, or unwelcome, they will not come back. They will go to the nearest ideology that offers belonging, even if it is built on denial.

Degrowth has to remember what it already knows intellectually: systems tip gradually.

That means degrowth must become better at combining vision with process.

It must learn from the very frameworks it sometimes criticises. The wellbeing economy and doughnut economics succeed at invitation. They create space for people to enter the conversation without needing a PhD or a confession. Degrowth provides the engine. But engines still need drivers. And drivers are human.

Pressure and Pathway: How Change Becomes Possible

For this synthesis to move from theory into force, the wellbeing economy and doughnut economics must become more explicit about what they are, and what they are not. If these frameworks are to gain real traction socially, politically, and economically, they cannot remain open ended visions that float above the question of power. They must define themselves as incompatible with continued growth in already wealthy economies and as requiring structural reductions in material throughput, energy use, and capital accumulation. Degrowth, in turn, plays a distinct and necessary role. Not as a competing destination, but as the pressure mechanism that shifts the Overton window and makes a wellbeing economy politically thinkable in the first place.

Degrowth does this through its linguistic framing and its willingness to name growth itself as the driver of ecological overshoot and social harm. By refusing euphemisms and rejecting the promise that efficiency or innovation alone can solve systemic crises, degrowth disrupts the taken for granted assumptions that underpin policy making. Its language forces a confrontation with scale, limits, and distribution, and in doing so expands the range of policies that can be publicly discussed. Proposals that once appeared radical or unrealistic, absolute reductions in material use, caps on resource extraction, redistribution of wealth and working time, begin to register as necessary responses to a clearly articulated problem. In this way, degrowth performs the political work of destabilising common sense, creating the space in which other frameworks can operate.

Within that space, the wellbeing economy and doughnut economics can play a complementary role. They translate disruption into direction. Where degrowth applies pressure, these frameworks provide a shared picture of what a post growth society is organised around. Care, sufficiency, ecological safety, and social foundations. They help institutions, communities, and publics imagine how life might function once growth is no longer the organising principle. This is what hostage negotiators call the golden bridge, creating a safe and dignified way for the other side to transition without losing face. But this tandem only works if all camps agree on a shared premise: that the current system cannot be tweaked into alignment through better indicators or narratives alone, but must be transformed through deliberate redistribution of power, resources, and decision making. Without this agreement, coordination collapses and fragmentation persists.

This is not a call to erase diversity or collapse difference into a single doctrine. It is a recognition that movements do not win by unanimity of thought, but by unity of direction. At present, the so-called new economic movements function more like an umbrella under which every critique of growth is placed, rather than a coherent framework aimed at a shared alternative. Degrowth, doughnut economics, wellbeing economy, commons based approaches, and ecological macroeconomics overlap in diagnosis, but diverge in strategy, often competing for legitimacy, funding, or influence. This pluralism is intellectually rich, but politically paralysing. Efforts leaks into internal differentiation rather than collective momentum.

What we should fear, and what we can already see emerging, is a synthesis that integrates all models into a single, softened vision that can be easily absorbed and neutralised. In the pursuit of coherence, difference is smoothed out, antagonism is dissolved, and politics quietly disappears. Under the banner of “living systems,” power, ownership, and accumulation are reframed as natural dynamics rather than structural causes of harm. This is how movements lose force. Not through open opposition, but through integration that drains them of conflict and direction. It is a familiar pattern, one that echoes how coordinated networks were able to diffuse and outmanoeuvre movements like Occupy by absorbing critique without conceding power.

The real choice is not between cooperation and confrontation, but between strategies that build power and narratives that dissipate it. Without pressure, visions drift. Without direction, pressure collapses. Only together, without collapsing into a single co-optable story, can these frameworks move from critique to consequence, and from ideas to irreversible change.

The Strategic Synthesis: Confront Power, Build the Bridge Without Diluting It

So here is the shared lesson, and it sits deliberately in the middle.

The wellbeing economy and doughnut economics must stop acting as if nudging power is enough. They must name structural realities directly and define themselves in ways that cannot be easily absorbed into green growth narratives, branding exercises, or institutional comfort. Without clear boundaries, vision becomes decoration.

Degrowth, in turn, must stop acting as if being analytically correct is sufficient. Structural critique alone does not build movements. Degrowth must engage seriously in coalition building, sequencing, and emotional intelligence, recognising that people move through stages and that political alliances are built deliberately, not discovered through purity.

This is the synthesis. We need confrontation and invitation, but without collapsing one into the other. We need red lines and on ramps, but without smoothing away antagonism in the name of coherence. We must be uncompromising about the destination while remaining strategically flexible about how different groups are brought into the struggle.

The neoliberal project did not win because it was morally superior. It won because it was coordinated, repeatable, culturally embedded, and ready when crisis created openings. Its strength was not correctness, but alignment.

If a post growth future is to become real, fragmentation is not an option. But neither is forced integration. What is required is alignment around a shared direction and a shared theory of change. Not because unity is aesthetically pleasing, but because movements that dissolve their internal tensions into a single, softened vision are easily neutralised.

The Lesson from Neoliberalism: Alignment Without Erasure

The lesson from neoliberalism is clear. A relatively small group reshaped the world not by winning debates, but by aligning ideas, institutions, and narratives around a common agenda. The same approach can be used for collective good.

But only with discipline. Only by distinguishing between vision and process. Only by accepting that different terms serve different strategic functions. And only by resisting the urge to collapse those differences into a single, co optable story.

Doughnut economics and the wellbeing economy help people imagine a future worth striving for. Degrowth explains why the current system cannot deliver it and how it must be dismantled. Post growth names the destination. None of these is sufficient on its own. Together, without being merged into one harmless synthesis, they form a coherent theory of change.

The missing piece is alignment. Not agreement on one word, but agreement on direction and sequence. Change minds first, build power second, change policy third. And above all, stop mistaking appealing to power for building power. One asks politely for permission. The other creates the conditions where permission is no longer required.

The economy is not a law of nature. It is a story reinforced by institutions, incentives, and power. Neoliberalism understood this. That is why it won.

At this point, the purpose of distinguishing between degrowth, wellbeing, and doughnut economics should be clear. The task is not to decide which framework is theoretically superior, but which configuration of ideas can actually move society. When debates remain at the level of conceptual refinement, they confuse intellectual differentiation with political progress. What ultimately matters is whether these frameworks together form a coherent sequence, from how we understand the world, to what we value, to how institutions are designed, to how change is made. Without that sequence operating across individual, organizational, and systemic levels, distinctions become inward facing and self referential. Terms only earn their relevance when they orient action forward, when they clarify what must change next, at what scale, and through which mechanisms. Otherwise, they risk becoming sophisticated descriptions of the present rather than instruments for transforming it.

If we want a different future, we must stop arguing about which word is most correct and start asking a harder question. What combination of vision, pressure, and politics can actually move society. The fire is real. The exit is visible. The only question left is whether we are willing to walk toward it together, speaking different words, but refusing to be absorbed into a single story that leaves the system intact.

Sources: Available in the pdf format of the essay, see LinkedIn profile of Kasper Benjamin Reimer Bjørkskov or Erin Remblance

.

Brilliant diagnosis of the fragmentation problem. I call it the Tower of Babel problem. You're right that we need alignment without collapsing into co-optable narratives.

But your "change minds first, build power second" sequence misses the coordination infrastructure layer.

You don't change minds - you relate to what people already know. These 300+ movements (there are SO many beyond just the four mentioned that are primed to coordinate) aren't confused about their direction. They're stuck in a coordination problem because they lack shared language, stories, and timing mechanisms.

The neoliberals didn't win by "building power" as a separate step. They built coordination infrastructure - think tanks, media relationships, coordinated messaging calendars. The power emerged FROM coordination, not before it. Coordination IS power. (And a recent AI development has the same emergent shape as this you might be fascinated to know, but this is still insider info atm)

We've run experiments this year proving this works in a specific order: coordinated storytelling across movements using bridging language (wellbeing economics, community wealth) creates frequency illusion effects that make alternatives feel inevitable. Viral content hitting 100K+ consistently because we're not "changing minds" - we're showing people solutions they already want exist everywhere simultaneously.

And most importantly, providing actionable pathways that fractally scale in small moves, because this is not only inspiring people to say "this is the kind of movement that changes world history," but giving them permission to take those actions. And that's where real systemic change emerges.

The missing piece you're pointing toward isn't better theory. It's coordination technology - shared rhythms, bridging terminology, and timing mechanisms that let these movements amplify each other without requiring ideological consensus.

Happy to share frameworks if useful. We're building this infrastructure now.

I think alignment around a “shared direction” is a lot easier than a “shared theory of change”, and doubt the proponents of neoliberalism ever agreed on a common theory of change (although I see it might appear so in hindsight).

After reading the essay I am not sure what you propose in practical terms. Who should sit down and agree on a theory of change? And would that theory apply to the whole world? One theory of change for Africa, China, USA, Russia, and the EU seems unreasonable to me.

Personally, as a European, I would suggest the EU starts defining a vision for a post-growth EU economy with inputs from all member states and cultural groups. That would, I imagine, prepare the ground for systemic change.